Sigrid Quack and Leonhard Dobusch comment on the election results of the German “Piratenpartei” based on their research project “The Copyright Dispute”.

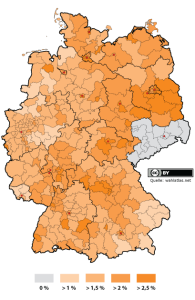

On Sunday, 27 September 2009, the Pirate Party running for the first time in German federal elections promptly won 2 percent of the votes. In some constituencies, particularly in university towns and urban centres, it gained up to 6 percent. In total, 850.000 voters cast their ballot for the Pirate Party (see official results and DW-World).

While this result does not bring the Pirate Party into the German parliament because of its 5 percent barring clause, this is nevertheless a quite impressive result for a young party which was founded only three years ago. Just to compare, the Green Party gained only 1.5 percent in its first run for German Federal elections in 1980, even though it had reunified a number of regional parties with experience in municipal councils and Länder parliaments. According to Forschungsgruppe Wahlen, an independent polling institute, the gains of the Pirate Party are part of a “historic gain’” of small parties in the last elections.

While this result does not bring the Pirate Party into the German parliament because of its 5 percent barring clause, this is nevertheless a quite impressive result for a young party which was founded only three years ago. Just to compare, the Green Party gained only 1.5 percent in its first run for German Federal elections in 1980, even though it had reunified a number of regional parties with experience in municipal councils and Länder parliaments. According to Forschungsgruppe Wahlen, an independent polling institute, the gains of the Pirate Party are part of a “historic gain’” of small parties in the last elections.

First signs of the Pirate Party gaining electoral support became visible in the elections for the European Parliament earlier on 7 June this year, where the Pirate Party obtained 0.9 percent (see also “Copyright Related Social Movements: Pirate Parties and the European Parliamentary Elections”). In the North Rhine-Westphalian communal elections on 30 August, members of the Pirate Party gained seats in the municipal councils of the cities of Münster and Aachen. In parallel to its public visibility and electoral support, the membership of the Pirate Party has been growing rapidly to currently close to 10,000 members, out of which about 8,000 joined the party during the last four months.

Still, this leaves interesting questions about what made nearly a million people vote for a relatively unknown and unestablished party, and what the perspectives of this party are for the next elections in North Rhine-Westphalia in 2010. Is the Pirate Party comparable to a “Biertrinker-Partei” (“beer drinker party”), as suggested by political scientist Oscar W. Gabriel (see pr-inside.com, German), and is therefore its success a short flash that will disappear as soon as it popped up?

In the following we will suggest that to be better understood, the development of the Pirate Party in Germany needs to be situated in a broader context: The gains of the Pirate Party build on both, a network of transnational activists criticising an, in their view, unbalanced extension of copyright protection and more localised social movements concerned with new data retention and surveillance plans. The internet is the place where these rather broad trends enter everyday life experience of people, and particularly those of having jobs in computing, software, creative industries, media, education, research, universities – not to speak of the palpable and rather concrete experiences of all those who wish to download music, share files and access open content in their free time.

Transnational context: How a file sharing server in Sweden leads to the birth of a party in Germany

Originally, “piracy” was considered to be something evil. As Sell and Prakash (PDF) convincingly argue, lobbyists in favour of stronger protection of intellectual property rights had used the term to describe and thereby delegitimize previously legal practices in (mostly: developing) countries. How come that pirate parties in over 20 countries manage to at least partially re-define the notion of “pirates” and “piracy” by using it successfully as a description of their idealistic and political actions? In a way, establishing pirate parties resembles the adoption and re-definition of previously derogatory terms such as “queer” (see Jagose) by the very group that is addressed by these terms.

In their self-description as “pirates”, the founders of the first pirate party, the Swedish “Piratpartiet”, followed the Swedish anti-copyright organization “Piratbyrån” (“The Pirate Bureau”). In 2003 the Piratbyrån had started the now famous website “The Pirate Bay”, which enables file sharing by indexing torrent-files and received enormous media attention around the “Pirate Bay Trial”. Not least this media attention led to the Piratpartiet’s success in the elections to the European Parliament, where they won 7.1 percent of the votes and became fifth strongest party, overtaking the old-established Left Party and the Center Party (see Wikipedia for details).

But the success of the Piratpartiet was not limited to ballot boxes. Established parties like the Moderate Party (Moderaterna) and Swedish Left Party (Vänsterpartiet) changed their positioning in the field of copyright in general and on filesharing in particular. What is more, the Swedish example initiated a series of followers in currently over 30 different countries, as listed at pp-international.net. One such follower is the German “Piratenpartei”.

But neither the Swedish nor the German pirate party had to start from scratch, several other organizations had prepared the ground for their mobilization; actually, pirate parties are part of a relatively broad and transnational social movement. The prevalent regime of strong intellectual property rights protection had come under attack by NGOs such as the ETC Group in the field of patents and Creative Commons in the field of copyright (see Dobusch and Quack, PDF). Wikipedia lists five “movements” in the field of “Intellectual property reform activism”, namely the Access to Knowledge Movement, Anti-Copyright, Cultural Environmentalism, the Free Culture Movement, and the Free Software Movement. It is the year-long activism of their proponents together with (partly: illegal) file sharing as a mass phenomenon that pirate parties all around the world build upon.

At least to some extent, this social movement context makes pirate parties more than a mere “single issue party”. Opposition to copyright and patents spans many different areas – from genetic engineered food and development politics (“biopiracy” and gene patenting) over education and science (Open Courseware, Open Access) to software, culture and innovation (Free Software, Free Culture, Open Innovation), and includes aspects of inequality in terms of access to immaterial goods in a so-called knowledge society. Furthermore, this bandwidth of issues may be complemented by local initiatives, as is the case in Germany.

Local context: Reminiscences of the campaign against “Volkszählung” in the 1980s

In spite of the transnational or even global character of these movements, pirate parties develop differently from country to country as they mix and co-evolve with local idiosyncrasies and movements.

Within Germany, some advocacy of the Piratenpartei evokes reminiscences of the civil activist campaign against the “Volkszählung” in 1983 (see wikipedia for details, in German and English). At that time, the plan of the German government of a population census was seen as intruding into the privacy of citizens and creating the technical potential for a “Big Brother Society” of state surveillance. These fears gave rise to the rapid creation of thousands of citizen action committee’s against the census, petitions signed by thousands of people, and a broad civil society coalition including representatives of churches, unions and civil society organizations like the Humanistische Union, and lead the German Constitutional Court (Bundesverfassungsgericht) in its decision (1 BvR 209/83) to formulate a basic right to “Informationeller Selbstbestimmung” (data privacy) which also shaped European policies in this field (see Newman 2008).

Some lose threads of this historical movement have recently been taken up by the German pirate party in their opposition against new legislation on data retention, online computer surveillance (see the Times for the UK-pendant to the German legislation) and Internet censorship by a so called “Access Impediment Act” (see also Bendrath).

Some lose threads of this historical movement have recently been taken up by the German pirate party in their opposition against new legislation on data retention, online computer surveillance (see the Times for the UK-pendant to the German legislation) and Internet censorship by a so called “Access Impediment Act” (see also Bendrath).

While tapping into the remaining scepticism towards technical surveillance by the state, which has grown after the German reunification due to decade-long spying by the East German “Ministry for State Security” (“Stasi”) as well as in response to new anti-terror legislation introduced following September 11, the new anti-surveillance activists in Germany do not principally reject using new technologies. On the contrary, the majority of German pirate party activists may very well be called “netizens”, who integrate new digital technologies in nearly every aspect of their professional and personal life. Differently to the general critique of technology in the 1983 census protests, pirate party activists reject technological surveillance because they want to use these new devices also in their most personal matters.

Future perspectives

Consequently, most of the German pirate party’s election campaigns also take place on or are at least organized via the Internet. A visit of the Piratenpartei’s website prior to the elections revealed the busy live of a beehive: While it is common for politicians of all parties to use online platforms like Facebook and Twitter to let their electorate participate in their everyday experiences, there is no other German party which made such innovative use of its website for coordinating the election campaign, from fund raising to plastering cities with posters and from meetings at regular’s tables to organizing public demonstrations. Christoph Bieber even calls this form of campaigning an “augmented reality game”.

While the focus on online campaigning not least followed from scarce financial resources, this may change due to recent election results, which crossed the 0.5 percent threshold required to get campaign funding from the federal government for the next elections. Party chief Jens Seipenbusch is already considering how to invest the funds for further mobilization (see DW-World). As it is appropriate for a party representing a growing population of young (and old) internet users, among the options discussed is not only the hiring of additional personnel to handle the party’s exceptional growth (see graph below), but also the acquisition of new software and equipment to facilitate online voting and discussion for a for members.

The (intentionally) very open mode of online campaigning, however, also has its adverse side-effects, such as maverick followers whose views might compromise the party, legions of “trolls” (see also Tina Guenther at sozlog, German) and a male bias: As opposed to the Swedish Piratpartiet, for example, which had several female candidates on its list for the European parliamentary election, its German counterpart is dominated by male computer professionals. A situation that inspired heated debates in the German blogosphere about whether feminists could vote for the pirate party or not (see, for example, danilola or maedchenmannschaft).

Antje Schrupp summarized her concerns in a blog post titled “Can a feminist vote for pirates?” as follows:

“There is a new party, rebellious, wild and strong-willed in their struggle against old frumps – and then they emerge as deeply sexist, and even worse, they don’t even seem to care about this. What shall we do now with the pirates?“ (translation LD/SQ).

A question not only open for feminists to answer, yet.

17 comments

Comments feed for this article

October 2, 2009 at 10:59

Sebastian Botzem

Dear Pirates,

just a short add on to your interesting and informative posting: in northern Germany, popular myth views pirates quite favourably, namely Klaus Stoertebecker (http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Klaus_Stoertebeker) who also appears to have been in Sweden at some point. As a buccaneer fighting the Hanseatric League he is seen more like Robin Hood than a self-serving criminal. An image suitable for social movements to draw on.

October 2, 2009 at 12:19

Britta Rehder

Very interesting article! But I am sceptical about the long-term success of the Pirate Parties. The major difference to the Green Parties of the 1980s is, that the Greens attracted people from several different social movements addressing different cleavages in society (feminism, peace movement, ecological issues). Whereas the Pirate Parties pursue a strictly liberal approach which is not very far away from the agendas of other liberal parties. For example, the German FDP has always rejected technical surveillance.

October 2, 2009 at 12:34

Britta Rehder

… One additional comment: the Pirate Parties are not liberal insofar as they reject strict property rights. But I don’t think that this will enhance their chances in a capitalist society in which property rights are holy.

October 2, 2009 at 12:54

leonidobusch

Thanks for your comments, Britta. While I am not sure about the long-term success of the pirate parties, either, I would not say that they pursue a strictly liberal approach similar to the German FDP – even when leaving aside the property rights issue. Not only did Christian Engström, the Swedish Piratpartiet member in the European Parliament, join the faction of the European Greens, but also is there a broad variety of economic concepts among pirate party activists and sympathizers, ranging from libertarians to neo-marxists.

My impression – stemming mainly from personal discussions and reading blogs of pirate party activists – is that the pirate party, while definitely not being anti-capitalist, is nevertheless critical towards capitalism and much closer to the Greens than to strictly (neo)liberal parties such as the FDP.

October 2, 2009 at 14:57

Sigrid Quack

Thanks all for these comments. I agree that the success of the Piratenpartei, and pirate parties in other countries, as A PARTY is an open question. I think that your comment, Britta, raises the interesting question of how to measure the success of a political party: Is it proportions of votes in elections, is the survival of the party, is it successful reprentation of its consituency in the parliament (measured as influencing politics and legislation), is it raising the attention of the public to problems in society, is it mobilising citizens to participate in political processes, …. (one can probably think about other dimensions)? For the moment, the pirate party resembles more a social movement than a “classical” party. Thus, the party might stimulate public debate about questions of who should own cultural goods and why they should not be accessible to all, as well surveillance issues (still represented by left liberal politicians such as Burkhard Hirsch or Gerhard Baum and Sabine Leutheusser-Schnarrenberger, but not prominent in the election campaign of the liberal party). By doing so, it might, like in Sweden influence other party’s policies on these issues. In short, all I suggest is that there is a mobilisation process behind the party which makes it unlikely to disappear in the short term. For other opinions see the interview under

http://www.readers-edition.de/2009/09/29/wozu-brauchen-wir-die-piratenpartei/

October 2, 2009 at 18:51

Britta Rehder

Dear Sigrid,

you’re surely right hinting at the different dimensions of how to measure a party’s success. But your article started with the observation that the Pirates won more votes than the Green Party did in 1980. This comparison suggested the idea that we might witness the emergence of a new player in the field. All I wanted to say is that I don’t think this will happen because – at least in Germany – I don’t see much more space for another left-liberal party. Therefore one could expect that the Pirates sooner or later will be absorbed, probably by the Greens, if I understood Leonard correctly.

I wouldn’t agree that the surveillance issue did not play a prominent role in the election campaign. We can already see how this issue becomes a major conflict line between the Christian Democrats and the Liberals.

October 4, 2009 at 19:13

tinaguenther

Dear Pirates, though I am not amused about the appearance and tone of the German pirate party and some of their fans in the days prior to the German election, I share Sebastian Botzem’s idea that the movement will continue and can eventually become a success, given the democratic foundations of the German Pirates are solid. Ultimately, Pirates’ result in the election is a strong signal to the established German political parties. They should begin a tough competition about what freedom is all about, what it means to be liberal in the best sense of the word (things like property versus commons, tolerance versus intolerance, ‘neoliberalism’ versus ideas of liberalism that include a firm commitment to social solidarity, the importance of privacy versus adequate measures to fight terrorism etc.). I hope it is not just wishful thinking that the Pirate Party, as it develops further, will force the established German parties to redefine their position with regard to freedom accordingly.

October 8, 2009 at 19:49

Helen Hartnell

So pleased to see serious discussion of this issue! Congratulations. I recently attended the election party at the Goethe Institute in San Francisco. Most of the people I spoke with there — German expats — had not heard of the Pirate Party and thought it was a joke. Obviously not!

October 13, 2009 at 12:30

philmader

Fascinating entry – today is the second time I’m reading it! The various mini-scandals in the past months about the right-wing statements of some senior members of the Piratenpartei just came to my mind… The party itself was quick to distance itself from such demands as to have an “independent inquiry” into whether the Holocaust ever took place, or from the interview of their vice president Andreas Popp with the notrious ultra-right newspaper “Junge Freiheit”, but the members in question never actually did. It will be fascinating to see whether or how a young party that claims to want to “overcome the left-right schema” of seeing the world will deal with such issues, and what definition of freedom they will evolve. In my opinion it would be dangerous to extend freedom word to include the revision of history and insulting of the victims of the Shoah.

October 16, 2009 at 22:06

Christoph Bieber

This might be of interest, too:

Pirates Board European Politics: The Internet’s First Political Party

http://techpresident.com/blog-entry/pirates-board-european-politics-internets-first-political-party

Although there are some flaws in this article (I´ve already commented on that at the techpresident.com-website), it brings issues, movement/party and discussion across the atlantic.

Let´s see, what´s next.

January 2, 2010 at 00:48

One Year Blogging about Governance Across Borders: Statistics for 2009 «

[…] Pirate Parties: Transnational mobilization and German elections […]

January 5, 2010 at 16:29

Bono Bashes File-Sharing: Learning from China’s Online Censorship? «

[…] evil music pirates. If I was a member of one of the growing pirate parties in Europe (see: “Pirate Parties: German Elections and Transnational Mobilization“), I could not thank Bono enough for such elaborate […]

March 19, 2010 at 19:09

Too Sexy for Being an Insult: Framing Piracy «

[…] the election success of European pirate parties (see “Pirate Parties: Transnational Mobilization and German Elections“), Sigrid Quack and I had already emphasized their success in redefining a derogatory […]

September 19, 2011 at 00:03

Boarding Berlin: The Pirate Party Triumph in the German Capital (FAQ) «

[…] Two years ago, the German Pirate Party won 2 percent in the German federal election (see “Pirate Parties: Transnational mobilization and German elections“). Today, they boarded Berlin’s state parliament with 8.9 percent of the votes and 15 […]

September 19, 2011 at 09:03

Fragen und Antworten zum Erfolg der Piratenpartei in Berlin | blog.sektionacht.at

[…] rund um Zugang zu digitalen Technologien und Reform von Immaterialgüterrechten ist (vgl. zum Thema transnationaler Mobilisierung). So gibt es mittlerweile in knapp 50 Ländern Piratenparteien, von denen die meisten auch Mitglied […]

April 5, 2012 at 18:34

Transnational Pirates #1: State of the Movement «

[…] social movements concerning intellectual property rights (Dobusch & Quack 2012 and “Transnational Mobilization and German Elections” on this […]

April 12, 2012 at 21:44

Transnational Pirates #3: Global Movement, Local Networks «

[…] and organizational networks. Furthermore, these results lead us to reject notions such as the Pirate Parties are a mere temporary phenomenon or a protest […]