The Andhra Pradesh crisis has been something of a turning point in public assessment of microfinance, with a suicide wave caused by widespread overindebtedness badly tarnishing the sector’s image in India as well as abroad. Some Indian politicians are now beginning to identify the idea of alleviating poverty with microfinance as “crap“.

Source: M‐CRIL Microfinance Review 2012 (vii)

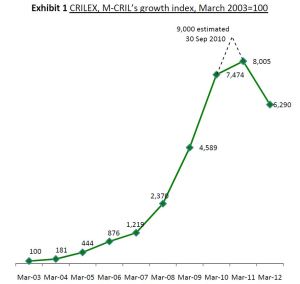

Microfinance in India remains in protracted decline since 2010 (see graph), although talk of “green shoots” and catharsis after “near-death experience” has been around for some time. The industry’s stance for the past two years has been to deny responsibility for any wrongdoings, downplay its role in precipitating the dozens of suicides, and claim that the AP government’s October 2010 legislation was a surprising and unjust crackdown on healthy practices. I have claimed otherwise.

Yet, fairly surprisingly, my new paper investigating the causes of the crisis, and a recent interview with SKS Microfinance senior managers come to some similar conclusions about the causes. In particular, both versions see the unregulated hyper-competitive market as a significant cause of the tragedy which led to microfinanciers’ troubles. How can this be?

The paper, written for a special issue on microfinance in the business journal Strategic Change, embeds the national and transnational processes which drove the Indian microfinance industry’s unsustainable growth into an analysis of the larger political economy of India. The industry was anything but healthy, digging its own grave by overlending as it was proudly reporting 99+ per cent repayment rates.

Although critical voices had questioned the soundness of the growth pattern and aspirations starting from the mid-2000s, the evident overvaluation and overcapitalization bubble was ignored by players and regulators alike. The 2010 crisis was what Srinivasan, author of several State of the Sector reports, called a “crisis by invitation”. (p. 52)

Overindebtedness, not government predation, caused the downfall

Starting with co-operative credit introduced by the British, India (like neighbouring Bangladesh) built up a legacy of credit-based social policy interventions through the 20th century. What drove many farmers and urban poor into the hands of the growing microfinance industry from the 1990s onward wasn’t any particularly good use for a loan, but rather the effects of the ambitious neoliberal reforms of AP, linked with population pressure and agricultural change, which eroded farmers’ and other vulnerable groups’ economic base (see in particular Taylor 2011). The microfinance industry profited from this toxic combination by feeding debt to an imperiled population in a system that was unstable and produced crises in 2005 and 2009, finally toppling in 2010.

Add the structural deficiencies of the Indian microfinance sector into the picture, and we recognise a hyper-competitive environment devoid of regulation, with microfinance institutions (MFIs) chasing market shares by lending to anyone who will take a loan. Interest rates remained unnecessarily high, generating abnormal returns which fed the rat-race between MFIs for success on the capital markets. External “agents” were often used to recruit new clients, internal controls hollowed out, and huge pressure exerted on clients. Before the crisis each one of the top six MFIs added 2,389 new active clients or 479 new joint loan groups (JLGs) every day,

so that by March 2010 statistically 35.9% of all households in AP had an MFI loan. The fact that the growth witnessed in AP was impossible on a “know your customer” basis is illuminated by SKS Microfinance — the sector leader — adding 4.17 million clients from April 2008 to March 2010, pushing its loans to 488 loans per loan officer by 2009. Also in the same period, the average borrower’s debt balance (toward each MFI) more than doubled; a debt accumulation compounded by multiple borrowing. (pp. 51-52)

Competition was driven by a seemingly unending supply of capital naively (and sometimes unscrupulously) seeking high returns, buttressed by Indian priority sector lending quotas. The stock market issue of shares in SKS Microfinance, the largest MFI at the time, which made founder Vikram Akula a multi-millionaire just months before the suicide wave, exemplified how the fish was rotting from the head down (various intransparencies and shady deals). At the same time it demonstrated the riches to be made from the tiny loans. The system was bound to collapse sooner rather than later, and finally did when the AP government pulled the plug to stop the suicides.

The competitive market was at fault, says SKS

In racing, “straight from the horse’s mouth” refers to information from a source so close to what’s going on, it may as well be the racehorse itself. Funnily enough, just as my paper goes to print, senior managers of the former sector leader SKS Microfinance have confirmed many of the above points in a rare press interview; straight from the horse indeed.

The managers portray the crisis as a “supply-side shock”, and in doing so confirm that the blistering prior growth wasn’t driven by genuine demand from borrowers, but rather by an ample supply of capital which only subsided after the government intervention spooked investors. Asked whether SKS would soon be applying for a banking license, the managers demonstrated a newfound recognition of the benefits from sensible and stable regulation, as opposed to their prior work to uphold a regulatory vacuum with facetious exercises in self-regulation.

While the crisis itself is still overall dutifully ascribed by SKS’ management to “political risk”…

The AP crisis was definitely an external event. It was a state intervention but this is not to say that everything was alright with the sector in 2010. (source)

… there is at least now an admission that the industry’s practices had become (self-)destructive.

The first mistake was all of us started as non-profit organizations and we embraced for-profit model for good reasons—to achieve scalability and sustainability. […] But when we embraced the for-profit model, we should have discarded the larger-than-life claims and mission statements like empowering the poor and eradication of poverty. The for-profit model doesn’t go with this.

When we had our initial public offer, people looked at our numbers, portfolio size and, most importantly, the individual incentive system like the ESOPS (employees stock options) and the salary levels. They were all relevant for a for-profit mainstream operation but the claim of eradicating poverty did not gel with that.

(… So it seems an open admission that microfinance is not about helping the poor is better than – perhaps – trying to reverse the mission drift; anyway…)

The second mistake at the sector level was that in 2009 and 2010, there was intense competition. There were 400-600 companies and even smaller firms were getting funds—be it debt or equity. If we go by the text book definition, intense competition should result in a price war but we had intense competition and no price war. Everyone was charging 31-32%.

The trouble was in the absence of playing the price card, process dilution became the selling proposition. Everyone was in the bar and all were drinking.

The customers also started playing one against the other on the processes and forced us to dilute them.

While this rhetorical shift of blame to the customers is baffling, the key admission from SKS’ management here – which underscores my paper’s analysis – is that the AP government’s legislative act only laid bare what was a set of pre-existing, fundamental problems in the industry. Much of its lending should never have been done, SKS now acknowledges. Better late than never.

Credit as an unsustainable surrogate

This is certainly far from a full-scale admission of responsibility for recklessly overindebting and exploiting clients to the point of suicide, but nonetheless a clear departure from the prior industry line that it was a government pouncing on a healthy industry which created the distress.

However, my paper and the SKS execs still differ on the ultimate legitimacy of the microfinance business in India; even though the latter may have admitted more than they intended in their interview. Where CFO Dilli Raj explains that his company’s recent troubles in the state of Gujarat arose because it “is a very progressive state and has a pro-business government but microfinance works better in markets where there is a density of rural poor”, this sounds very much as if microfinance in India thrives on dysfunction and desperation – which in fact is the conclusion of the paper. Microfinance in India acted only as a surrogate for developmental policy, rather than as part of a package for positive economic transformation.

In conclusion:

The proximate causes of the AP crisis were largely home-made, and the AP government’s intervention was at most an enabling factor. Warning signs that Indian MFIs’ spectacular growth and profitability rested on overwhelming indebtedness of clients – the industry’s success in fact being merely a giant debt bubble – were amply present long before the crisis, but were blissfully ignored and later quietly forgotten. […]

In the Andhra boom, the music played until a sufficient number of suicides forced the government to intervene. But the fundamental causes of the crisis lay with India’s historical tradition of (ab)using debt as a tool of social policy. If there is one key lesson to be learnt from this more contextualized account of the Andhra Pradesh microfinance crisis, it is that deeper-seated social problems cannot be resolved with an infusion of debt, and that industries built on that premise are bound to fail eventually. (pp. 60-61)

Or, to summarise in the words of the above-mentioned politician, the entire premise may be “crap”.

Mader, Philip (2013): Rise and Fall of Microfinance in India: The Andhra Pradesh Crisis in Perspective. Strategic Change 22, 1-2, 47–66.

(phil)

9 comments

Comments feed for this article

March 6, 2013 at 15:49

Daniel Rozas

Philip – would love to comment, but too bad your paper is behind a paywall… I would just say one thing: while I see no issues with casting the AP MFIs in the role of a villain (especially in the pre-AP crisis period), it does not automatically follow that the AP government must then be the hero. Yet that is exactly what you seem to do here, as in “until a sufficient number of suicides forced the government to intervene”. While you decided to reference me for a tiny fragment from a piece that dealt with something else entirely, I think you might benefit by looking at my rather more extensive work on AP, going back to 2009, when I first raised the question of a bubble in the state.

In the context of microfinance, I cannot think of a single action by the AP government that could be construed as being motivated by a genuine desire to protect the poor, and I don’t think using them as pawns in a political game qualifies under that category.

Two articles I suggest you read are:

You’ll find more on AP here: http://www.danielrozas.com/tag/andhra-pradesh/

March 7, 2013 at 13:25

Phil

Hi Daniel, Sorry about the paywall issue, what can I say… I’ll make sure you get a copy. You’ll see I cite your work in there, rather gratefully.

I think the misunderstanding here is about cause-and-effect rather than motivation. Far be it from me to ascribe anything but self-serving motives to the AP government. The poor are vote banks, and in a democracy like India it has to be re-elected; facts which explain the rise of microfinance in AP as much as they do the fall. Inaction on the microfinance suicides reports was a poor option for the government, I argue. So not “hero”, but rather: “opportunist doing the right thing for the wrong reasons, and in a blundering and short-sighted way”. Better? Phil

March 7, 2013 at 16:44

Daniel Rozas

Hey Phil — yes, better. Though I’d take issue that what AP gov’t did was the “right” thing at all — I can imagine a 100 different approaches that would’ve been vastly superior to the one they took. Instead of improving things, they simply swapped one bad situation for another.

Thanks for the paper — look forward to reading it, and will surely share my feedback.

Cheers.

Daniel

March 7, 2013 at 11:51

Milford Bateman

Daniel

I think you have perhaps misunderstood what Phil is saying here. I don’t read into what he writes here (I have not seen the article yet) as saying that the AP government was a hero.

In fact, it is most certainly NOT just the greedy CEOs in the top five MFIs that are to blame for the wanton destruction to the AP economy and to its poor population: the AP government is one of the bad guys in this story too. The AP government was warned by its local personnel on numerous occasions in 2004-5 that a microcredit bubble was emerging in rural Krishna county and some other locations, one that would be very bad for the poor when it inevitably popped. But the AP government did nothing to deal with it, other than to draw up an agreement with the top five MFIs and their greedy CEOs to ‘guys, be more careful in future’ (i.e., cut interest rates a little, reduce the number of multiple loans, lay off the heavy handedness when collecting a loan, etc). But when this agreement was torn up by the MFIs almost as soon as the ink on it was dry, the AP government did nothing at all to reprimand the MFIs for their obvious bad faith. It then got worse in 2008-9 when many local and some international journalists began to warn about a microcredit bubble in the urban areas, notably WSJ journalist, Ketaki Ghokale, and then later yourself, STILL the AP government did nothing. Some have suggested that the MFIs bought off the regulators and forced them into inaction. Maybe. Other said the AP government liked the temporary boost to consumer demand, and the higher local tax take, that all this cash was (temporarily) underpinning. Possibly. Anyway, the fact remains that the top five MFIs and their greedy CEOs selfishly and knowingly created a massively destructive microcredit bubble, yet all the while this was going on the AP government knew who was involved, what they were doing, why they were doing it and how they were doing it, but it refused to take any meaningful action whatsoever. When they finally got their act together in the face of the damage done, the cam eup with the famous ordinance. But that, of course, was closing the barn door after the horse had bolted long since…

But there is also an important difference here that also needs highlighting. Whereas the CEOs of the top five MFIs were selfishly and proactively destroying the AP economy, and each was jockeying for position to be the first to get spectacularly rich from an IPO, the inefficient AP government was not responding to the challenge created by these CEOs. A ‘non-response’ is a flaw, sure, I agree, but its not nearly so serious as the greed-driven actions and deliberate frauds to be found at the very top of the microfinance sector in AP. So comparing the actions of the MFI CEOs to that of the AP government is a little like comparing the crimes of Bernie Madoff to those of of Eliot Spitzer. The former actually created the AP meltdown: the latter did nothing to stop it.

Milford

March 7, 2013 at 13:24

philmader

Milford, thanks for your commentary which underscores the ambivalence of the AP government’s actions. From its perspective (motivation, once again, being a difficult thing to prove!) microfinance appears to have been a useful thing; until one day it wasn’t. Hence the sudden and dramatic change.

In a way this highlights the difference between the blog genre and scientific paper genre. While the blog may read more like a “hero and villain” story, the paper is less about exculpating the government and laying blame on SKS (whodunnit?) than it is about the inevitability (or low evitability) of crises in hyper-competitive unregulated environments populated by overcapitalised actors with a near-angelic (self-)image. Yes: incidentally the type of environment which was (at least until recently) treated as the best possible environment for microfinance by donors and policymakers and CGAPs alike.

Understanding the complex and more subtle processes which led to the AP crisis, which extend way beyond the deliberate and purposeful actions of the government and the MFIs, is key to evaluating the potentials and drawbacks of alternative modes of doing microfinance.

March 12, 2013 at 15:26

The Youngest of the Microentrepreneurs: An intervention in the debate on child labour |

[…] industry-initiated self-regulation in microfinance; where it has failed, governments have tended to step in, as microfinance practitioners should be well aware of. But at the very least, clearly stating the […]

January 2, 2014 at 13:03

Blogging about Governance Across Borders: Statistics for 2013 |

[…] In partial agreement with SKS on what caused the Indian Microfinance Crash […]

January 1, 2015 at 13:23

Blogging about Governance Across Borders: Statistics for 2014 |

[…] In partial agreement with SKS on what caused the Indian Microfinance Crash […]

February 13, 2017 at 19:17

Rainbow of Links : Stuff I am Reading – Timed Impulse

[…] In partial agreement with SKS on what caused the Indian Microfinance Crash (Governance across Borders) […]