Dave Itzkoff hit the nail on its head with the following opener to his New York Times article on the heirs to Sherlock Holmes in 2010:

“For a 123-year-old detective, Sherlock Holmes is a surprisingly reliable earner.”

In a more recent guest post at the 1709 blog, Miri Frankel reports about a new legal battle with regard to the copyright expiration date of some works of Arthur Conan Doyle, the creator of the fictional character Sherlock Holmes:

In February Leslie Klinger, a Los Angeles attorney, filed a lawsuit against the estate of Sir Arthur Conan Doyle — the creator and author of a series of fictional works featuring legendary investigator and crime-solver Sherlock Holmes. Mr Klinger is the author of numerous books and articles relating to the “Canon of Sherlock Holmes” […] For years, the Conan Doyle Estate has demanded and collected licensing fees from authors who created works drawing from or based on the Sherlock Holmes character or other elements from the world of Sherlock Holmes. […] But Mr Klinger’s view, and the view of other, sympathetic authors who have created new stories based on elements from the public domain works of Sir Conan Doyle, is that these licensing fees are not necessary, and the Conan Doyle Estate should not be allowed to threaten them with lawsuits to extract licensing fees. The Complaint asserts that only new, original elements first published in the stories that remain under copyright protection are still protectable; copyright no longer protects, however, any elements that had already been published in earlier Sherlock Holmes works, so all such elements are now in the public domain.

Interestingly, Klinger makes his arguments not only in court but has also launched a website entitled “Free Sherlock!“, where he is even asking for donations “to offset legal fees and expenses of the litigation.”

The core argument of the Conan Doyle Estate is, in turn, that the character of Sherlock Holmes “is a unified literary character that wasn’t completely developed until the author laid down his pen.” In case this interpretation of the law were upheld in court, all copyright elements related to the character of Sherlock Holmes would remain protected until 2023, the date upon which the final story published by Doyle enters the public domain. To underline the willingness to enforce their rights until the bitter end, the Conan Doyle Estate prominently points to “the Sony Bono Copyright Extension Act of 1997”, which extended protection terms to 95 years following the date of publication.

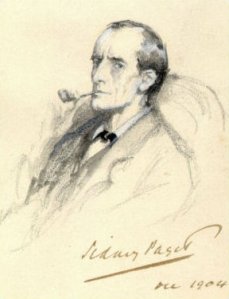

However, what I find even more ‘thrilling’ about this case is the fact that, as explained by Frankel, “the Conan Doyle Estate also asserts trade mark rights in the word mark Sherlock Holmes and the silhouette image of a pipe-smoking Sherlock”. And while there is at least some discussion spanning the fields of copyright and patent law (see, for example, “Private Ordering in Copyright and Patent Law: Property-Preempting Investments“), intersections of copyright and trademark law are rarely debated. Is it possible to uphold a mark designation, which roots in a public domain work? The answer to this question is important because trademarks theoretically remain valid forever or at least as long as the owner actively uses and defends them.

If the heirs of Arthur Conan Doyle have their way, maybe – in addition to strategic patenting in high-tech markets – we will also observe a rise in ‘strategic trademarking’ by the entertainment industry to make the usage of public domain works more difficult for potential competitors.

[Update, December 28, 2013]

In a first ruling on the case (PDF), Chief Judge Rubén Castillo grants Klinger’s motion for summary judgement

with regard to Klinger’s use of Pre-1923 Story Elements and denied with with respect to Klinger’s use of the Post-1923 Story Elements.

This decision effectively prevents the heirs of Conan Doyle to extend protection via copyright means; however, it does not address the issue of trademark law.

(leonhard)

Leave a comment

Comments feed for this article