For this year’s Wikimania (26-28 August, Buenos Aires) I submitted an abstract of a paper comparing transnationalization processes and community relations of Creative Commons and Wikimedia. In this series I present some work in progress.

While the now famous online-encyclopedia Wikipedia was founded shortly before Creative Commons in 2001, its organizational carrier – the Wikimedia Foundation – was founded about half a year after Creative Commons had formally launched its first set of alternative copyright licenses in December 2002. Both organizations share the fundamental vision of creating and promoting a global “commons” of freely available digital goods. Wikimedia hosts a framework of hardware (webspace and bandwith), software (the wiki-engine “MediaWiki”) and legal rules (copyleft licenses) for several projects of commons-based peer production such as Wikipedia, Wikibooks or Wiktionary. Creative Commons, in turn, delivers a set of open content licenses to – not only, but also – legally enable and foster such commons-based peer production projects as put forward by Wikimedia.

Interestingly, independent from one another, both organizations very soon after their foundation started to transnationalize by developing a transnational network of locally rooted organizations. In a way, this strategic coordination of legally and financially independent organizations resembles what is called “strategic networks” in the realm of business research (see, for example, Gulati, Nohria and Zaheer 2000). Their strategies of building such an organizational network were however quite distinct.

Creative Commons, on the one hand, started to legally translate (“port”) its license modules into local jurisdictions – an unprecedented move in the field of open content licensing. For porting the licenses into other jurisdictions and for promoting the licenses among creators, Creative Commons teamed up with local affiliate partners. In all jurisdiction projects, one affiliate is responsible for the legal translation of the license (“legal project lead”) and – in the majority of jurisdiction projects – another one predominantly deals with the community of license users (“public project lead”). The relationship between the focal Creative Commons organization and its affiliates is probably best described as a form of “political franchising”: The affiliate organizations and Creative Commons sign a “Memorandum of Understanding” (MoU) that predominantly deals with Creative Commons as a brand. License porting procedures in turn are standardized but not formally regulated. All other aspects of the affiliates’ work such as local events, funding or thematic priorities are up to them to decide (for details see Dobusch and Quack 2008).

Wikimedia, on the other hand, exclusively relies on newly founded and legally independent “Wikimedia Chapter” organizations as a transnationalization strategy. New chapters have to be approved by Wikimedia’s “Chapter Committee” to become officially recognized by the Wikimedia Foundation. While Creative Commons partners with different types of organizations – ranging from university law schools over non-profit civil society organizations to profit-oriented firms –, nearly all Wikimedia chapters are relatively similar, non-profit member-organizations. Similar to Creative Commons Wikimedia also requires its chapters to sign various formal agreements regarding the use of name and logo.

As a “natural” recruiting ground for local Wikimedia activists and, hence, founders of local Wikimedia chapters serve Wikipedia language projects: from their very start, Wikipedia and its sister projects were designed to be multilingual, which soon led to the development of different language projects. Although participants in language projects are not necessarily geographically close, soon local “regulars’ table” of very active contributors emerged, which then were the basis for further engagement in the realm of chapter organizations.

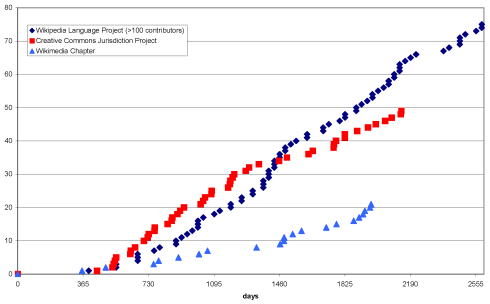

The Figures above and below depict the growth of these three types of transnational entities, namely Creative Commons’ jurisdiction projects with ported license versions, local Wikimedia chapter organizations and Wikipedia language projects reaching the 100-contributor-threshold. The data in the second figure below is adjusted for differences in founding dates.

Although both Creative Commons and Wikimedia experienced astonishing transnational growth in the first years of their existence, Creative Commons managed to establish more than twice as many local jurisdiction projects with ported license sets (49) than local chapters had been approved by the Wikimedia Foundation (21) by the end of 2008. The relatively slow organizational transnationalization of Wikimedia is even more in need of explanation when compared to the growth of Wikipedia language projects. Before the first Wikimedia chapter was launched in Germany in 2004, 17 different language projects had already reached over 100 regular contributors, some of them even over 1,000 contributors.

These differences in both transnationalization strategy and dynamic can at least partly be explained with reference to differences in organizational constitutents and tasks:

First, Creative Commons was founded by an “epistemic community” (see Haas 1992) of lawyers, which provided relatively privileged access to resources of their hosting organizations such as university law schools, law firms or think tanks.

Second, the multiplicity of individual backgrounds in the Wikipedia community, which is clearly a strength – if not a precondition – for Wikipedia as a project, poses an additional challenge for building formal organizational structures. While members of Creative Commons’ epistemic community already shared a set of principled and causal beliefs, notions of validity and a common policy enterprise, the foundation of Wikimedia chapters requires a shift in identity from being a “mere” contributor to commons-based peer production (Benkler 2006) to becoming a (kind of) political activist. But it is this “identity shift” that leads people to take over administrative tasks, which are key for any formal mode of organizing.

This is related to, third, the issue of the affiliate organizations’ major tasks: whereas porting and maintaining Creative Commons licenses is a clear-cut task with recurring elements such as license versioning, Wikimedia chapters – at least in the beginning – had to find and define their role. Besides, Wikipedia language projects not only provide a recruiting ground for potential Wikimedia activists but also offer enough possibilities for engagement without becoming a member of any formal organization.

(leonhard)

4 comments

Comments feed for this article

September 7, 2009 at 16:05

Mayo Fuster Morell

Hello Leonhard!

Thank you for the excellent post.

I would like to make two comments:

1) When you said: “the multiplicity of individual backgrounds in the Wikipedia community, which is clearly a strength – if not a precondition – for Wikipedia as a project, poses an additional challenge for building formal organizational structures”. Perhaps, we could see it in the opposite direction. That is: the more formal organization of the Wikimedia Chapter is a way to deal and a way to create a frame in which very diverse approaches can coexist in a chapter group. As you point at the post, CC “activist” have more similar background (law related, etc.), in this conditions an informal frame could be a good one, but when you have lawyers, but also economist or librarian, and even when you have right-wing and left-wing people involved at Wikimedia projects, perhaps a more clear-cut structure could be needed in order to bring all of them together in a chapter group.

2) Concerning your third point, I was also wondering that it could be useful to consider that create and maintain the “common” at Wikimedia (that is the encyclopedia, dictionaries etc.) requere much more effort than to maintain the CC licenses; this could also affect the “energy” and type of approach remaining for the chapter type of tasks. Furthermore, Wikimedia commons (the encyclopedia etc) have an economical value, which the license does not. In sum, the activities of the Wikimedia in contrast to the activities of CC could also explain the need of organizational solutions for its transnationalization. Still, I think your comparison between CC and Wikimedia transnationalization is very useful and can bring good light on the weaknesses and strengths of each approach.

Thank you! Mayo

European University Institute – Phd Candidate on Governance of digital commons:

Research: http://www.onlinecreation.info

September 20, 2009 at 21:10

Wikimania 09 Review: Quo Vadis, Wikipdia? «

[…] free knowledge in general and supporting local Wikipedia projects in particular (see also “Wikimania Preview #2“). World’s first and most resourceful chapter is Wikimedia Germany and most other chapters […]

November 1, 2009 at 16:59

Re-Negotiating Rules of Governance: Wikipedia Notability Debates «

[…] the community of contributors but rather define their role as purely supportive (see also “Wikimania Preview #2”). So far, most of Wikipedia’s rule setting processes have solely been undertaken online […]

October 12, 2010 at 10:51

Money Buys You Standards? The Gates Foundation’s Push for CC-BY «

[…] the other being adaptation of licenses to local jurisdictions (see also “Wikimania Preview #2“) […]