Excerpt from “The Political Economy of Microfinance: Financializing Poverty”, Chapter 2, A Genealogy of Microfinance. (see other excerpts here)

Microcredit allowed the well-institutionalized tool of credit programming to remain inside mainstream development policy, despite a diminished role for governments, and despite the fall from grace of subsidies. In reality, microcredit programming merely shifted the subsidies and state involvement one level “up”: no longer were loans to the poor subsidized and publicly supported; now the organizations which lent to the poor were subsidized and supported.

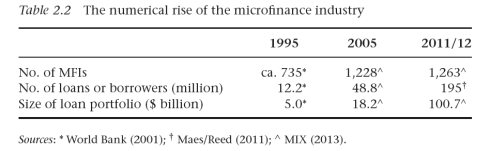

Sources: World Bank (2001); Maes/Reed (2012); MIX (2013) = Basic MIX MFI Data Set, as of 26 December 2013.

Reliable data on microfinance from before 2000 are very rare. In the mid-1990s the World Bank surveyed the sector and counted over 900 “institutions which offer microfinancial services” (around 735 of them being “proper” microfinance institutions), each serving at least 1,000 clients. The list included seven large banks and one NGO. The survey tallied around $5 billion in outstanding loans. However, the vast majority of MFIs were recently founded NGOs which placed little, if any, emphasis on savings and received over two-thirds of their funding from donors (see Figure below). This group was fast-growing. The World Bank (2001: 4) noted: “Much of the impetus for this growth comes from donor organizations and NGOs embracing microfinance as the latest tool in development and poverty reduction. Due to the increasing availability of donor funds, microfinance institutions have grown rapidly.”

Standardizing microfinance, financially

The World Bank’s decision to support microfinance primarily through its International Finance Corporation (IFC) arm, whose purpose is “financing private sector investment, mobilizing capital in the international financial markets, and providing advisory services” (IFC 2011), affected which type of organizational model would become dominant: MFIs that were willing and able to manage funds that were channelled from mainstream financial markets were favoured.

(Data source: combination of figures 3 and 7 from World Bank (2001); see references below)

To further aid the transmutation of NGO-MFIs into for-profit, credit-focused, financially streamlined entities, the World Bank founded CGAP. Its self-described mission at the time was to “nurture and spread the experiences of pioneer retail institutions and practitioner networks in micro-finance … disseminate lessons learned by practitioners, foster and mainstream micro-finance into donor policies and operations, particularly in the World Bank, contribute to supportive policies for micro-finance institutions (MFIs), and invest in eligible MFIs” (CGAP 1999: 7)

CGAP was founded in a phase when the World Bank, reacting to prolonged harsh criticism from civil society, publicly sought to reinvent itself (while retaining its role as a policy-based lending institution) as the “Knowledge Bank” for development. Begun in 1995 as a “consortium of donor agencies and microfinance practitioners working together to bring microfinance into the mainstream” (Bhatnagar et al. 2003: 1), CGAP conformed well to this new image.

As Ananya Roy (2010: 45–46) clarifies [in her highly insightful book which deepens many of these arguments], despite its image of diversity and independence, CGAP has no legal existence outside the World Bank; essentially it is a World Bank entity that embodies “not only the poverty agenda of the 1990s, but also the power of what can be understood as the ‘Washington consensus on poverty.’ … it is CGAP that controls how microfinance is understood, or what we know about microfinance. In this sense, CGAP controls the truths about microfinance.” Housed at the World Bank’s headquarters in Washington, it became a focal point for the international microfinance industry due to the reviews that it performed, which could strongly influence future funding flows to MFIs (Adams and Raymond 2008). As a World Bank evaluative report explained,

Between 1995 and 1998, CGAP played a pivotal role in developing a common language for the industry, catalyzing the movement towards best-practice performance standards, and building a consensus among its varied stakeholders. Reporting standards for MFIs were defined. It developed various operational tools for practitioners and donors on management information systems, business planning, financial projections, appraisal format, and audit standards. It also developed a performance-based funding approach for MFIs through partnership agreements based on the MFIs own performance targets. (Bhatnagar et al. 2003: 4)

In other words, CGAP functioned globally to standardize and homogenize microfinance on a private sector template, and moreover a template that was specifically oriented towards the financial market and financial investors. CGAP promulgated strategy publications such as its famous “pink book”, Micro and Small Enterprise Finance: Guiding Principles for Selecting and Supporting Intermediaries, and formulated successive “Consensus Guidelines” [including this example] on how different aspects of microfinance should work. It effectively became a regulatory and policy institution in the microfinance sphere at a formative stage, challenging and largely displacing the older Grameen-type model, to foster microfinance’s globalization.

…

The counsel for NGO-MFIs was clear: become independent, become a bank; not seeking formal, private investors would be a breach of mission. “The formal [financial] sector, not the informal sector, has the potential to make microfinance competitive, and thus to contribute to economic growth and development” (Robinson 2001: 218). While some authors, such as Jonathan Morduch, remained doubtful, claiming that the benefits of subsidizing MFIs should at least be contemplated because “programs like the Grameen Bank tend to have broad externalities” (Morduch 1999: 247), these voices were increasingly marginalized.

A case in point for how the World Bank’s involvement profoundly shaped the development of microfinance into a thoroughly financialized sphere was the Grameen Bank itself. It too came under pressure from funders, rating agencies and CGAP, having officially posted a profit every year (except one) since its inception, but in fact having been massively subsidized. Morduch (1999: 235–236) claimed that Grameen’s steady performance was a facade, since “categories and expenses are moved around to ensure that Grameen posts a modest profit” every year, while by regular accounting standards and banking practices it would have lost around $26 million – 30 million per year. Furthermore, Grameen’s practice of tolerating overdue loans drew criticism from rating agencies, and the IFC withheld a planned loan securitization deal in 1998.[1]

Feeling the pressure of the financial markets pressing into microfinance, from 2001 on, Grameen was forced to lower its costs and improve its collections rate (Dowla and Barua 2006), which it did by abandoning the group-based model, reducing its range of loans and allowing borrowers to borrow additional finance. As the Wall Street Journal spotted, the latter aspect was simply converting overdue loans into new “flexible” loans which were then reported as being up to date. Above all, the new “Grameen II” model required an “obligatory contribution” to be paid, called the “Grameen pension scheme”. These compulsory savings effectively amounted to an interest-free loan from the borrowers to the bank. The reinvented Grameen project also branched out into non-banking services, such as GrameenPhone, photovoltaic solar systems and marketing yoghurt for Danone. Thus Muhammad Yunus’ new hobby horse “social business” was born.

…

The New Economy of Microfinance

The “dot.com bubble” demonstrated that issuing shares against hypothesized future earnings allowed firms to dramatically expand their capitalization and generate large payoffs for founders and managers. Many MFIs, meanwhile, were generating significant real profits and had a bright outlook, but they still had little access to markets in share capital. This began to change with the microfinance investment market’s heightened visibility under CGAP’s stewardship, which reconfigured MFIs as interesting financial investment targets.

…

By centralizing market information, the founding of the Washington, DC-based Microfinance Information Exchange (MIX, or Mixmarket) in 2002 opened a new chapter in the commercialization and marketization of microfinance. CGAP created MIX as an online database to collect and provide investor-oriented information about MFIs, in line with the World Bank’s self-perceived mission as a knowledge broker.[2]

MIX data are collected globally, catering explicitly to investment decision-makers to allow them to search for and compare MFIs via information that is primarily related to their financial performance. MIX rhetorically has recently also emphasized “social performance management”, but it still excludes relevant indicators from its quantitative tools for comparing MFIs. Social performance is presented by MIX as “not a separate area of an MFI’s operations, but is very much linked with financial performance”, such that an “enabling operating environment” and voluntary standards (“do not harm”) already should guarantee social performance (Pistelli 2011).

By the mid-2000s the streamlined, minimalist, explicitly commercial variant of microfinance was rapidly becoming the dominant model; not necessarily by total size yet but in terms of donor and investor backing. A report by the Council of Microfinance Equity Funds in 2004 identified at least 124 explicitly private, commercial, regulated, shareholder-owned MFIs (Kaddaras and Rhyne 2004). The 71 MFIs that were investigated in greater depth grew from $2.3 billion in assets in 2004 to $6.8 billion in 2006. As of August 2006 some 75 specialized microfinance investment funds, of which 28 were “private”, existed and were seeking investment targets.

The general trend claimed for the sector was that “private sources of capital are indeed supplanting, or will replace, public direct investment in commercial microfinance, a crucial step on the path to accessing large pools of private, investment capital … [M]any of these social investors have adopted a much more commercial outlook” (Rhyne and Busch 2006: 17).

Footnotes:

1. The late Daniel Pearl researched this story for the Wall Street Journal. Years later, notably, Daniel Pearl memorial intern Ketaki Gokhale forewarned about the impending microfinance overindebtedness crisis in India.

2. MIX is located at the World Bank, chaired by a CGAP staffer, and financed and controlled primarily by the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation, Omidyar Network (run by the eBay founder), MasterCard Foundation, IFAD, Michael & Susan Dell Foundation, Citi Foundation, Ford Foundation and Deutsche Bank.

Mader, Philip: The Political Economy of Microfinance: Financializing Poverty. London: Palgrave-Macmillan, June 2015.

Mader, Philip: The Political Economy of Microfinance: Financializing Poverty. London: Palgrave-Macmillan, June 2015.

(phil)

3 comments

Comments feed for this article

July 5, 2016 at 09:39

Paywalled Microfinance Data: Is the global “Knowledge Bank” dead? |

[…] Information Exchange”, or “Mixmarket.org”) was created by the World Bank’s in-house-but-arms-length microfinance governing body, CGAP, to improve the transparency of the microfinance industry. Since […]

January 14, 2017 at 20:49

Continuing Microfinance’s momentum | Invest Impactly

[…] to a World Bank report, microfinance has built a solid track record as a critical tool in the fight against poverty and […]

March 23, 2017 at 18:46

Benjamin Onigbinde

Microcredit financing still remain a very strong tools to reduce poverty especiallyin a country like Nigeria where their is hugh inequality in income distribution. What we really need a unique model for microfinance subject to each political and economic environment.